Hello, friends. If this post interests you, please consider getting a copy of the book–Lives of Unforgetting (What We Lose In Translation When We Read the Bible, and a Way of Reading the Bible as a Call to Adventure). This puts food on my family’s table, and it makes me very happy to know the book is being read and used. Thank you for enjoying my posts!

Now on to the post…

—————————————————-

Stories that Live in Our Blind Spot

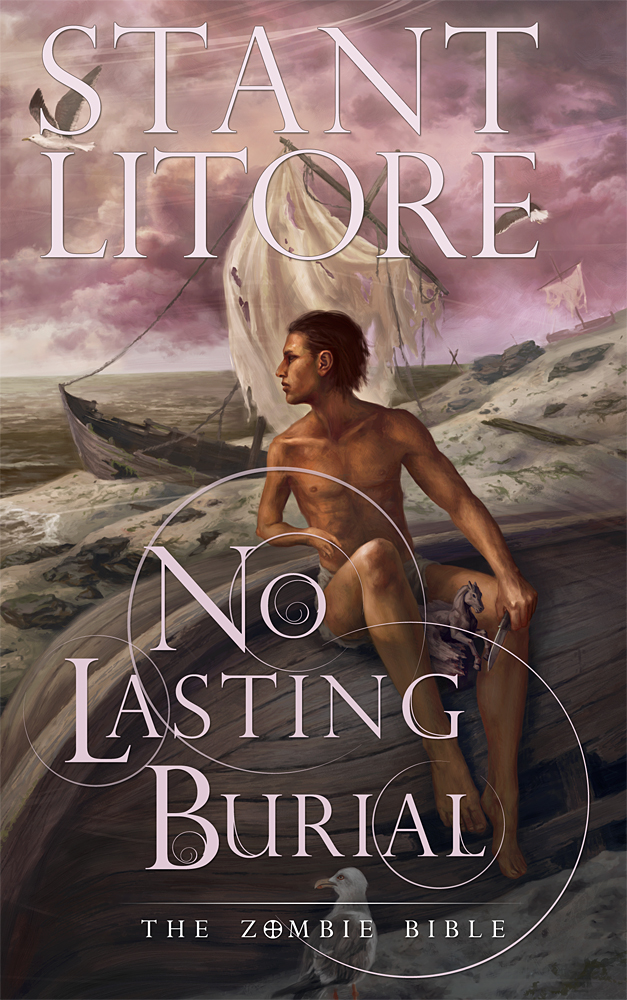

I write because I love stories, because I can’t go a day without telling a story or listening to a story. And as a child I encountered the Bible as a wondrous collection of shocking, horrifying, empowering, and troubling stories (sometimes, all four at once). When I embarked on The Zombie Bible, I wanted to share these stories, I wanted to make them new again, I wanted people not to walk past them but to live the horror and the wonder that I found when I read them. At the risk of sounding like a bully, I wanted to make readers cry.

I suspect that the majority of people in the U.S. ignore biblical stories. Religious people ignore these stories because, most often, they read merely for examples to corroborate or elaborate on what they’ve been taught. Secular people ignore these stories because, as a rule, they are unwilling to separate these ancient stories from the political slogans and agendas that refer back to them. To me, this is a tragedy. We are talking about one of our oldest and most diverse treasure-houses of stories, and it is the one such treasure-house that everyone talks about and no one really experiences.

These are horror stories and wonder stories, but we’ve largely forgotten that. In many cases, these stories were written to amaze us, or shock us, or move us. A crucifixion is horrific. A child sacrifice is horrific. These stories try to shock us awake and then invite us to ask really tough questions, necessary questions. I wanted to bring these stories to readers in such a way that they would horrify and amaze us again, move us again.

These stories deserve our attention, and we deserve the opportunity to let them touch our hearts and bring us to tears or anger or joy. We deserve to experience these stories as more than just political slogans or ‘life application’ self-help messages. The shock and grief of zombie horror is a way of letting us do that. It’s a way of taking us back out into the heart of the storm on the lake, to that moment when the waves are high and the sky is crushing us down with its dark weight, God is asleep, and we are hanging on to the gunwale for dear life, learning who and what we are.

How Not to Read (Seriously)

Let me try to explain what I mean more clearly. If you’re reading this, skip any part that gets tedious.

I think that most people, whether religious or secular, assume that you should read the Bible as one coherent narrative, novel, or history book. This is true whether you’re ransacking this text for a consistent religious doctrine or whether you’re trying to dismiss it in entirety.

But it isn’t one narrative.

It’s a whole nest of different texts from different times in which different people struggle to understand both God and humanity. Whether you “believe” in God or not — whatever your relationship (or lack thereof) to religion may be — the Bible provides a polyvocal record (a record consisting of many voices) of man’s developing understanding of man, ethics, and God.

This record opens with two ethical statements in Genesis 1:

- God looked on creation and pronounced it to be “good.”

- Male and female, we were each created in the likeness of the divine.

The thousand-odd pages that follow consist of 66 books (slightly fewer, slightly more, depending on which Bible) that debate these two ethical propositions (and others), across three continents (Asia, Africa, and Europe), three languages (Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek), and nearly a millennium of writing. You have a collection of legal texts, historical chronicles, poems, sermons, letters, testimonies, hagiographies, collections of proverbs, and dream-stories that wrestle with what these ethical statements mean, what these statements imply about God or about people, and whether/how/in what ways these statements might be lived and practiced in real life.

The Bible is an ongoing wrestling match, not a plotline.

Let me give you an example.

Strangers in the Land

You probably recognize Strangers in the Land as the title of my third novel, a nightmarish story of zombies and genocide in 1160 BC. It also refers to one of the core ethical statements in the Old Testament, one repeated again and again throughout the book of Exodus. Moses the Lawgiver instructs the Hebrews that, as they were strangers in the land of Egypt, they must treat the stranger in their own land well. There must be one law, both for the home-born and for the stranger. Strangers’ rights must be protected, vigorously — because the Hebrews, too, were once strangers in a strange land, and because the Hebrew and the stranger are both made in the likeness of the divine.

Now this ethical proposition flies in the face of some of our most basic instincts. We would rather fear the stranger, wall the stranger out, or possibly get rid of them; we want to protect our own. But Moses says no, you have to “shelter” the stranger.

One way to read significant passages in the Old Testament is to read them as dozens of different views of how the Hebrews struggled with two directions that often appeared contradictory: Shelter the stranger on the one hand; on the other, keep your own people safe and secure as well as separate and sacred as a “chosen people.” An ethical conflict that we get to watch in action:

- Exodus is the story of the wrath of God falling upon a nation that fails to shelter the stranger.

- In Joshua, tribes of Israel invade the promised land, displacing strangers

- In Ruth, a stranger from a strange land immigrates to Israel and is, at first, treated horribly — shunned by the Israelite women, starving, in danger of rape in the fields. Yet she is the heroine of the tale (and an ancestor of Jesus). The man who marries her is a man who goes out of his way to shelter the stranger.

- In the erotic poem, Song of Solomon, the Shulammite bride is a stranger in the land, and she is not liked. Other women in the city taunt her; the watchmen find her in the night and beat her. Yet her lover and husband finds her breathtaking. The poem is a breathtaking song of their union.

- In Daniel and Esther, the tribes again try to survive as strangers in someone else’s land, facing genocide, slavery, and several attempts simply to annihilate their language, their names, and their way of life.

- In Ezra, a priest demands that the people of Israel, who have newly returned to the land and have taken strange wives, cast their wives away as strangers, shunning them.

And so on, back and forth. In some accounts, the view that is privileged is “shelter the stranger.” In others, the view that is privileged is reject the stranger — violently, if need be. In the New Testament (in Galatians), Paul says that there is no Greek, no Hebrew, no male, no female, no master, no slave in God’s sight. In other words, race, gender, and class are seen as arbitrary and manmade distinctions. But then Paul has to wrestle with how to make this practical. What if a Christian woman has married a man who worships the old gods? What then? He wrestles with the issue, indicating what he thinks is right, and concludes with the direction that his readers must search their own hearts.

They must wrestle with it.

As readers, these stories, poems, and letters invite us into the wrestling match. Because make no mistake, we have to ask the very same questions that were asked thousands of years ago. Are we to shelter the stranger? How does this impact our views on immigration? How does it effect what we do when our child brings home someone of another race for dinner?

“Who is my neighbor?” one listener asks Jesus, and gets a very uncomfortable story in response. Who am I responsible for loving and sheltering?

You can take any number of ethical statements proposed in the Bible, and watch it get wrestled with, generation after generation, story after story, letter after letter. The Bible is not a consistent plotline or a manual; it’s a record of centuries of intense wrestling and it is an invitation for us to wrestle — openly, honestly — with these ideas. Ideas that have shaped and troubled our world. Ideas that are radical and important.

He Wrestles with God

In fact, the word “Israel” literally means “He wrestles with God.”

Think about that.

I mean, really think about that.

What if reading the Bible is not an act of taking in information (which you may then either adopt or reject), but an act of wrestling? How might that be a different reading activity (maybe an exciting one — regardless of whether you are religious or not)? What if the reading experience is supposed to be tense and contradictory and sometimes laden with horror, and what if that isn’t a bad thing?

What are we wrestling with, when we read the Bible?

Well, God, clearly — regardless of whether or not God exists.

We’re also wrestling with ourselves — with our own assumptions.

And we’re wrestling with the dead. With our past, which always (if we ignore it) rises up to devour us.

Wrestling with the Dead

There is a 1800-year-old Judaic tradition of reading the Old Testament which stands in stark opposition to the literalism of modern fundamentalist Christianity (and of much modern reading, in general). This tradition survives today in the conservative movement in Judaism and rabbinical scholarship (not to be confused with what “conservatism” means in America). This tradition celebrates the text without treating it as some type of novel or character profile, but as a treasure-house of cultural stories from the ancestors that need to be questioned and wrestled with — precisely because how we approach these stories has an impact on who we are and how we decide who we need to be.

A reader in this tradition is expected neither to accept tales of genocide in the Old Testament nor to reject them, because both are irrelevant to the goal of reading: which is to engage with one’s ancestors, what they felt and believed and hoped and feared, to wrestle with your dead for a while, learn from them, and talk with them, as part of a dialogue through which we create or attain wisdom for the present.

Our dead are different from us — even though they, like us, may have endured exile and privation and even though they, like us, may have experienced love and loss. By listening to our dead, we become better able to listen to the living — who are also different from us.

Relearning How to Read

Unfortunately, we’re taught to mine the Bible for information or models for behavior; it is treated as a static document, rather like instructions on how to assemble a bookcase. Maybe it is recognized to be more difficult to read and interpret than the typical bookcase assembly instructions, but in the end, we treat it as that kind of document — except that we are what is being assembled — and we either accept or reject the Bible depending on whether we like the shape we think these instructions will assemble us into.

In fact, we’re taught to read almost everything that way. Unless we have escaped this trap either by means of voracious reading on our part or some college instructor’s insistence, we tend to read even works of great literature in search of their “moral” or their one right, or best, interpretation. We go into stories looking for their end result, whether that end result is “True love conquers all” or “A good man is hard to find” or “Christ will save your soul.”

We aren’t taught that reading can be an act of wrestling.

If you look at a standard, American Christian study bible (let’s say the ESV Study Bible — beautiful translation, awful study aid), what you find is text at the top of the page, and annotations at the bottom of the page, in which one preacher or editor footnotes difficult passages and explains exactly what they mean.

I was shopping for a Bible once, in a religious bookstore, and the woman shopping next to me asked for my advice. “I want a study bible with clear notes,” she said, “so I’ll know what it means and I won’t have to think about it.”

We’re most often taught to read this way — as though every question in the book has an answer and only one answer and one of our fellow human beings will tell us exactly what that answer is. Infallibly.

Let’s compare this to a rabbinical study bible — the Etz Hayim, a Hebrew/English parallel text with annotations at the bottom. It is laid out just like a Christian study bible. But there’s a big difference. The annotations at the bottom might footnote a difficult passage and then run through five examples of how different people have read that passage in different centuries. Some of it is brilliant. Some of it is beautiful. Some of it is thought-provoking. It’s all meant to prompt you to wrestle with the text yourself, to ask smart questions and figure out what it means, not be told what it means.

That’s a beautiful, intelligent, exciting way to read.

How Do We Get There?

I think we start by making the stories real again. Whether we start (or end) as religious or atheist or agnostic readers, if we’re going to read at all, we need to encounter the stories — not as chapters in a novel, but as hundreds of stories that are all tackling related questions.

We need to read about Ruth in the fields gleaning scraps of food, as a single woman with a widowed and ailing mother-in-law, and we need to feel her fear and her desperate hope.

We need to read Jeremiah’s words as he howls in the street about the child sacrifices on the Hill of Tophet, and we need to feel his horror when he cries, “I see the blood of children on your skirts!”

And we need to watch Ezra banish the women and let ourselves feel very, very uncomfortable. Not just dismiss it or explain it away. Actually look at it, wrestle with it. And then ask ourselves some hard questions.

We need to read and feel — not just let these stories be some kind of commercial for a political program, nor source texts for a troubling religious dogma that some of us feel obligated to disinherit, nor even a religious instruction manual that is all about us. We need to go to these stories as we go to a date, a tense but hopeful encounter with people who are both like and unlike us, people who are other than us, and let ourselves be drawn into their lives for a while.

These stories have made me cry. And laugh. And shiver.

And they have challenged me to seek deeper relationships with my fellow human beings, with the dead who came before me, and with God. They have helped me work out my faith and my tradition with fear and trembling.

They have invited me to ask tough questions.

I think that’s partly what they’re for.

Stant Litore

———————————————–

Want to read more? Get Lives of Unforgetting: What We Lose When We Read the Bible in Translation, and Way to Read the Bible as a Call to Adventure.